Babe went to spoken-of haunts: everywhere from the Ronald #3 mine where her ancestors worked to the Mt. Olivet Cemetery where Jessee, his son Thad, daughter Rusia, and grandson Roy are buried. There was so much history written in Roslyn’s soil, and the fact that her loved ones were part of it was a story that bore telling.

“I realized that history had been made here,” she wrote in her introduction to The Donaldson Odyssey: Footsteps to Freedom. “My family had worked here and was part of that history and the history of Roslyn, Washington. I felt tears beginning to fill my eyes.”

The fruits of her labors became known as The Red Book in honor of its striking red cover. Babe shared the book with her extended family and gifted a copy to the Roslyn Historical Museum for those interested in a more in-depth analysis of the family trees and reflections on the Donaldson family lines.

“The Red Book is pivotal. It was written 30 years ago with what resources Lillian had available,” Butch said of his relative’s dedication. “She did a magnificent job collecting the documentation for such comprehensive research. She really set in motion forthcoming research our family would like to do on our heritage.”

What’s substantial beyond Babe’s devotion to publishing a 300+ page family anthology is that she did so before the convenience of digitized records available online. Babe and a few loved ones, including her cousin, Lenora Bentley, rolled up their sleeves and made the phone calls, sought the records, booked plane tickets to Tennessee, and asked the questions that collectively provided them with a strong foundation of family knowledge.

Lenora recalls Babe generating financial support for the project through creating and selling t-shirts at family reunions with a book title that could be the family’s mission statement: The Donaldson Odyssey: Footsteps to Freedom.

Karla Jackson, Jessee’s great-granddaughter said that although she hasn’t reread The Donaldson Odyssey in quite some time, “I’m [still] in awe of The Red Book.”

Babe’s daughter, Tia Forest, was in her twenties when her mother took up the substantial task of researching the family’s past. She recalls going to the archives with her mother a few times and says of the experience, “She didn’t want to sugarcoat the past. We still have people finding out they are Donaldsons. We’re a very diverse family, and a lot of us don’t look Black. You never really know what [ethnicity/race] people are.”

Tia said that her mother’s refusal to deny her African American ancestry left a lasting impression when she was a little girl. “She told me ‘Don’t ever pass for what you’re not.’” Babe fought three days to change Tia’s ethnicity to “Negro” from “White” on her birth certificate. “To this day, I put ‘Black’ on medical records. When people assume I’m Caucasian, I correct them,” Tia said.

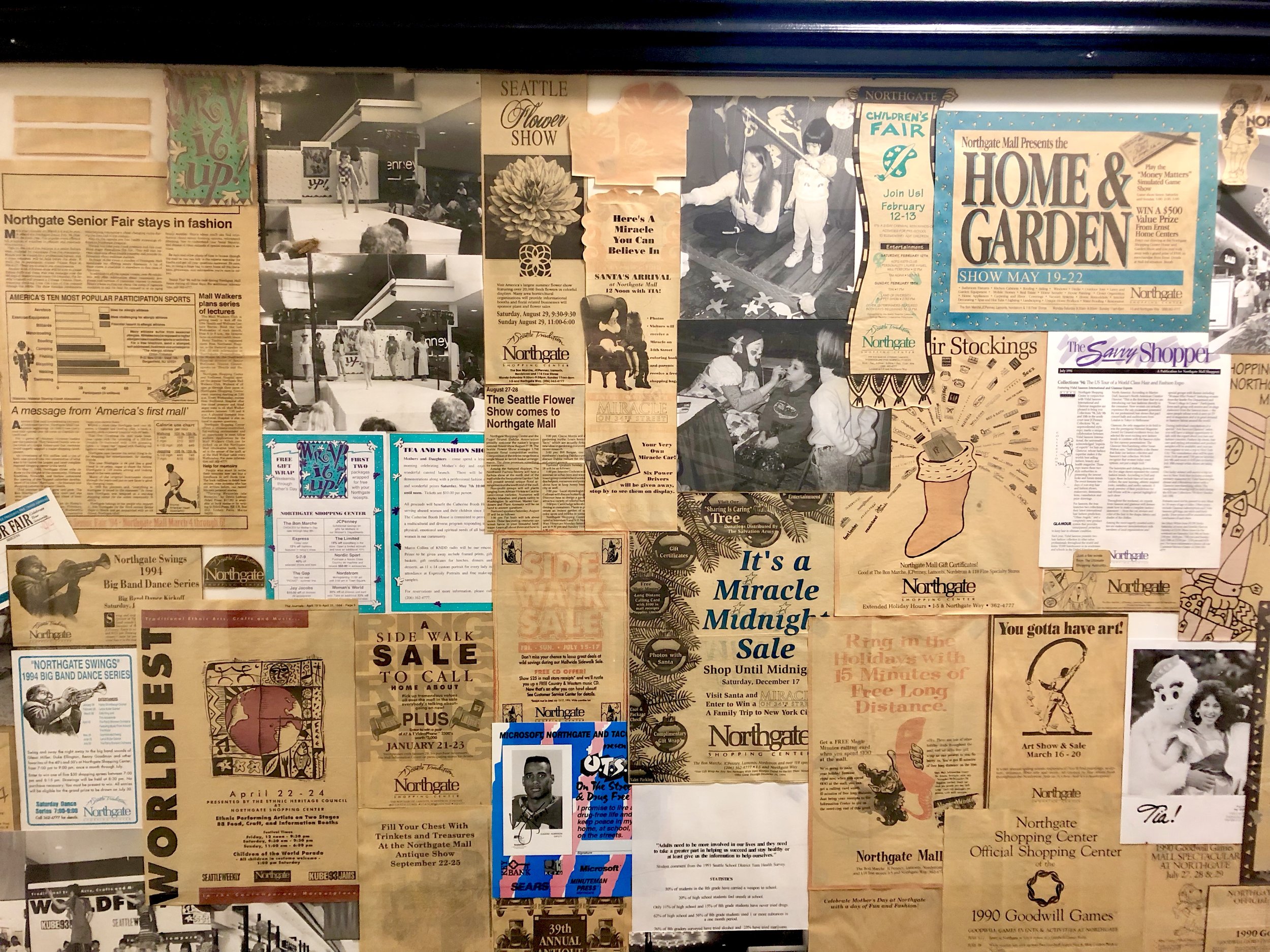

Tia, who is often asked if she’s Creole or Redbone in the clubs she sings in, says that she doesn’t mind people’s inquisitive natures. If they’re really interested, “I’ll sit them down. My mother taught me to never cut a pass, and I don’t. I’ve never allowed people to make racial slurs in my house. I automatically accept people for what they are.”

Tia credits her mother for being a woman of honesty and kindness. “She was a sweetheart and a beauty, but you better not cross her.”

Babe undoubtedly drew on some of the Donaldson steadfastness to see the anthology through to completion, and her relatives are especially grateful some 30 years later.

“Babe laid an incredible framework, and we are honored to be filling in the gaps today,” said Ryan of his continued quest to bring the Donaldson story to light. He’s come to experience the exploration of the past as a “guided journey,” as he follows in Babe’s footsteps and compares stories with other Washington Black pioneer families. Babe said she had a “powerful urge to know more about this family,” and Ryan knows exactly what she’s talking about.

Turns out that Babe faced resistance on her quest to uncover Donaldson family history. Her cousin Lenora said, “When she went down south, she was told not to dig too deep into the past. I don’t know who it was that threatened her in Tennessee. But let’s face it, some of our [white] ancestors didn’t want to bring up the past or know how bad it truly was.”

“I want to continue and pick up where [Aunt] Babe left off,” said Paula Terrell, Lenora’s daughter. “I was close to my aunt and mother when they were working on it, and it’s connected hundreds, if not thousands of us together.”

Paula said that the pervasiveness of the Donaldson presence in Washington state has sometimes meant learning that people she knew as co-workers or friends are, in fact, family members. For instance, she worked with Al Smith, Butch’s father, back in the 1980’s, left on a Friday, saw him at a family reunion over the weekend, and came back to work on Monday calling him “Uncle Al.”

“Because of that book, I realize the importance of knowing your family,” Paula said with conviction. “There’s pride in knowing where you come from. It adds value to each and every one of us.”

No matter who discouraged her discoveries, Babe remained steadfast to further uncover her family’s story. She wasn’t interested in what any naysayers tried to do to derail her efforts and spent countless hours compiling information on relatives across the family trees.

As a result, hundreds of descendants know who their family patriarch was and at least some of the trials Jessee and Anna weathered to provide them a future of hope and freedom. The family understands this rare gift, compared to fellow African American families who lack such detail about their descendants’ lives.

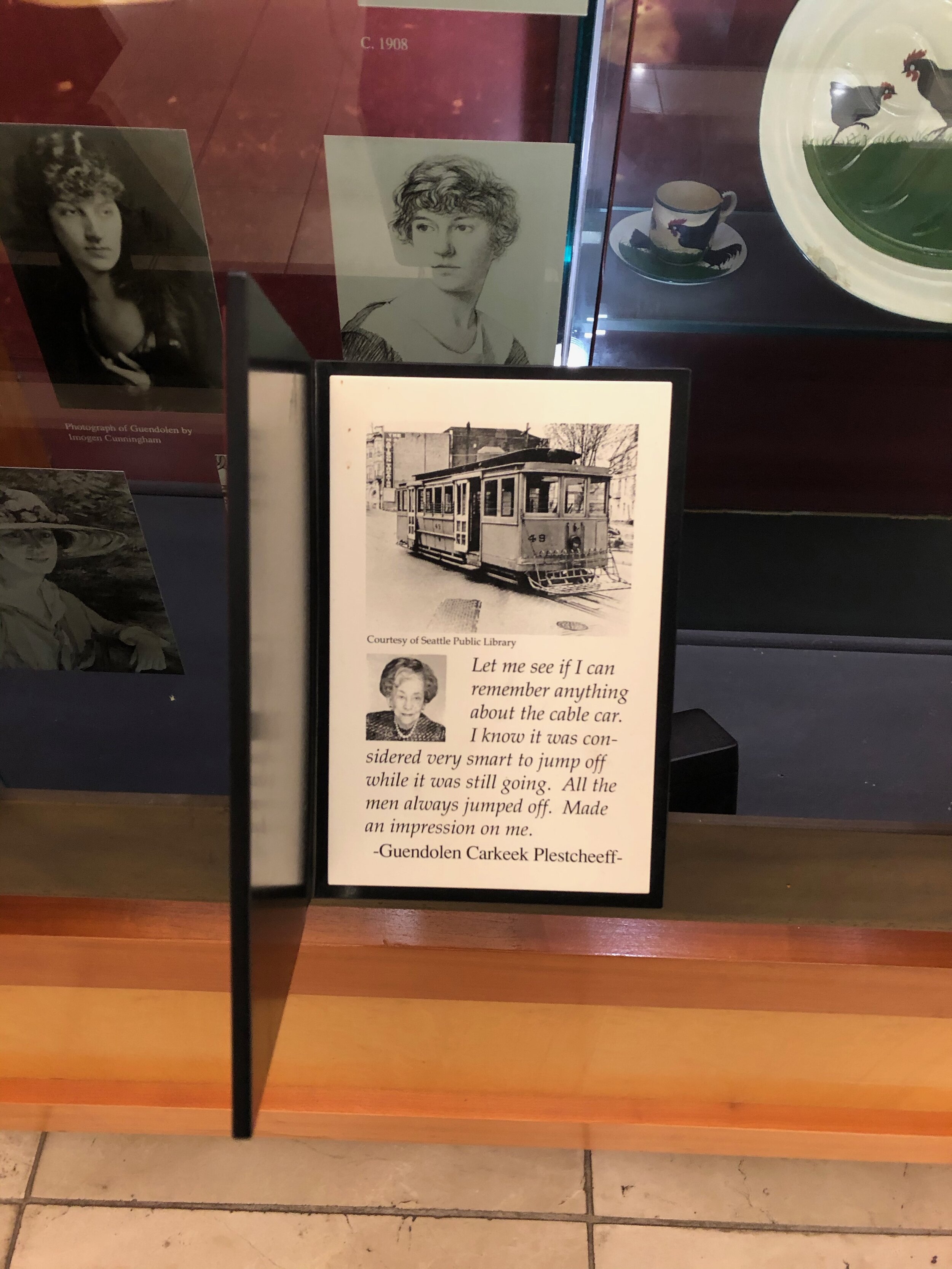

Ryan discovered an earlier edition of The Donaldson Odyssey within the preserved lectern from the AME (African Methodist Episcopal) Church at the Roslyn Historical Museum little more than a year ago. This edition includes photos and information that today’s Donaldsons are uncovering for the first time.

Considering how new connections are made all the time from The Donaldson Odyssey, the family narrative remains an evergreen wellspring of insights.

To anyone who sits down to read it, its pages outline an incredible journey from an Alabama plantation to postbellum Tennessee then coal mining company towns in Washington state.

Across generations, the Donaldsons are still finding themselves amidst significant phases of national and local history. This coming Saturday, August 13, members of the family anticipate attending the Roslyn Black Pioneer Picnic. They look forward to connecting with other descendants of the courageous African American men and women who arrived west by train many years ago.